Abstract

Parenting children with special abilities is not defined by diagnoses such as autism, ADHD, or dementia—it is shaped by environment, access to care, cultural beliefs, and the emotional resilience of families. While the neurological foundations of these conditions are universal, the lived experience of caregiving varies dramatically across countries, healthcare systems, and social structures.

This shift recognizes a vital truth: a parent’s response is not just a part of home life; it is a powerful medical intervention. When parents understand how to support their child’s unique brain, they can actually change the child’s life path. This article combines the latest science with practical advice to help families move from just coping to truly thriving.

The Continental Support Gap

Visualizing the Access to Early Intervention & Functional Support across 7 continents. Data reflects the availability of WHO-standard caregiving resources per region.

While North America and Europe have high “Systemic Support,” Africa and parts of Asia lead in “Community-Based Resilience.”

Click legend items to toggle data sets. Compare “Current Access” against the “WHO Recommended” path.

Caregiver Resilience Matrix

Evaluating the five pillars of Parental Wellbeing. This chart maps the balance required to sustain long-term caregiving for a child with special abilities.

Resilience is not “toughness”—it is the availability of scaffolding. Burnout peaks when “Personal Respite” falls below 20% capacity.

Data synthesized from the Parental Stress Index and caregiver quality-of-life meta-analyses.

Source: WHO World Report on Disability / Global ECD Survey / Harvard Health

Step 1: Framing the Challenge

“Special ability” is a broad term. It covers conditions that affect how a child thinks, communicates, behaves, or remembers. In India alone, roughly 1 in 8 children between the ages of 2 and 9 live with at least one of these conditions.

For many families, the journey begins with a “Diagnostic Odyssey”—a long, often exhausting search for answers. In India, this journey is made harder by a lack of specialists and a lingering social stigma that wrongly views these differences as “bad behavior” or “poor parenting.”

Our Central Thesis: Success in parenting children with special abilities is not about making them “normal.” It is about “neurological scaffolding.” This means the parent acts as a support system—much like a physical scaffold holds up a building—to help the child navigate a world that wasn’t built for their specific type of brain.

Step 2: The Core Science of Caregiving

I. Regulation Before Correction

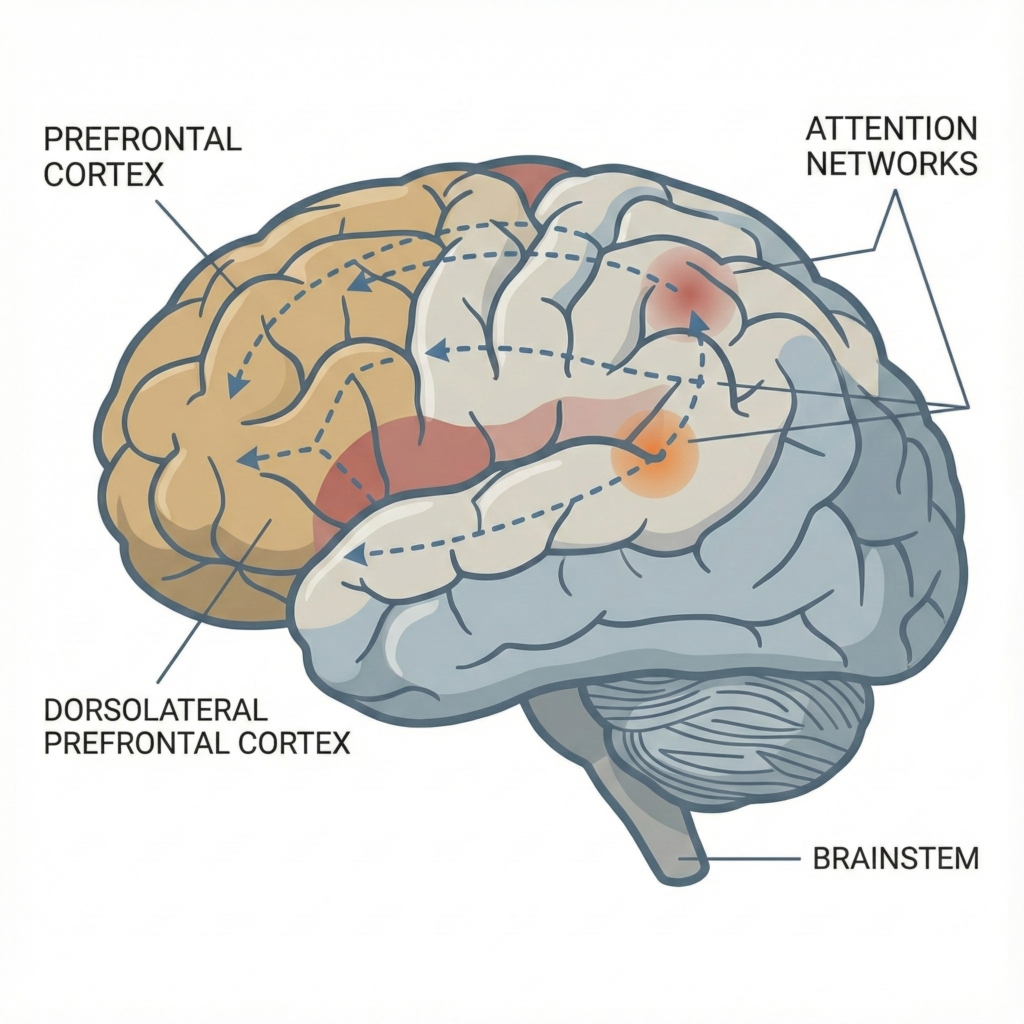

The most important lesson from modern neuroscience is this: many “difficult” behaviors are actually signs that a child’s nervous system is overwhelmed. This is called “dysregulation.”

Children with neurological differences often have a very sensitive “internal thermostat.” Small noises, changes in routine, or strong emotions can trigger a “fight-or-flight” response.

- The Co-Regulation Secret: Humans have “mirror neurons.” If you are calm, your child’s brain will eventually try to match your calm. If you are angry or stressed, their brain will match that, too.

- The Rule: You cannot teach a child a lesson or correct their behavior while they are overwhelmed. You must help them get calm first. Regulation always comes before learning.

II. Stop the Comparison Trap

Parents often feel a deep sense of failure when their child doesn’t hit “average” milestones at the “average” time. But milestones are just statistical averages—they are not a grade on your child’s worth or your parenting.

- Individual Growth: Research shows that children do much better when we focus on their personal growth rather than comparing them to others.

- The New Goal: Success is “functional gain.” If a child who couldn’t communicate starts using a single sign or a picture board, that is a massive, life-changing victory. It doesn’t matter if other kids their age are writing essays; for your child, that picture board is progress.

III. Building the “Scaffold” (Environment)

A child with executive function issues (trouble planning or focusing) sees the world as a chaotic mess of data. You can help by “scaffolding” their environment to make it predictable.

- Visuals are Key: Use picture schedules. Knowing what happens next reduces the “cognitive load” on the brain and lowers anxiety.

- Sensory Safety: Many of these children hear sounds louder or feel lights brighter than we do. Creating a “quiet corner” or using noise-canceling headphones isn’t “spoiling” them; it’s giving their brain the quiet it needs to function.

Step 3: Navigating the Indian Context

Raising a child with special abilities in India comes with specific hurdles, but also specific strengths.

The Power of Advocacy

India’s Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act, 2016 changed the game. It gave families more legal rights to school support and medical resources. However, getting these rights often requires the parent to become a “warrior-advocate.”

In bigger cities like Delhi or Bengaluru, you might find a full team of doctors. In smaller towns, you might have to be the “case manager” who coordinates between the school and the local doctor. This requires staying informed and pushing back against anyone who says your child “just needs more discipline.”

Breaking the Stigma

Cultural shame is a heavy weight. Many parents feel pressured to make their child “act normal” to avoid judgment. Science tells us that “masking” (hiding their true self to fit in) causes massive stress and long-term mental health issues for the child. Moving toward a “strength-based model”—where we celebrate what the child can do—is the best way to protect your family’s mental health.

Step 4: The Parent is a Patient, Too

We often talk about the child’s needs, but the parent’s health is just as important.

- The Stress of a Soldier: Studies show that parents of children with complex needs have stress hormone levels similar to soldiers in combat. This is not because you are weak; it is because the job is incredibly demanding.

- The Burnout Cycle: If a parent burns out, the child’s behavior often gets worse because they lose their “anchor” for co-regulation.

- The Medical Necessity: Taking a break (respite), talking to a therapist, or joining a parent support group is not a luxury. It is a vital part of your child’s treatment plan. You cannot pour from an empty cup.

Step 5: When to Call the Doctor

Caregiving is a long game, but sometimes you need to call for backup. Seek a clinical review if you see:

- Regression: They lose a skill they already had (like speaking or using the bathroom). This needs an immediate check-up.

- Unstoppable Outbursts: If meltdowns are becoming more violent or more frequent despite your best efforts.

- The “Wall”: If you, as the parent, feel you can no longer stay calm or present with your child.

Conclusion: Connection Over Perfection

Children with special abilities don’t need “perfect” parents who have all the answers. They need parents who are “present.”

Your job isn’t to fix them; it’s to understand them. When we stop looking for a “cure” and start looking for a “connection,” the dynamic in the home changes. By using science-based strategies like co-regulation and environmental scaffolding, you aren’t just managing a disorder—you are building a life of dignity and joy for your child.

Evidence-Based Summary

- Global Impact: Neurodevelopmental disorders affect up to 15% of children worldwide (The Lancet Global Health).

- Best Practice: “Parent-mediated” therapy (where parents are taught the skills) is often more effective than clinic-only therapy (Cochrane Reviews).

- Economic Reality: Supporting parents reduces the long-term cost of healthcare for the entire system (Harvard Review of Psychiatry).

Medical Disclaimer

This article is for educational purposes only. It is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult with a doctor or developmental specialist regarding your child’s specific needs.

Pingback: 7 Teen Suicide Warning Signs Parents Often Miss

Pingback: Autism Spectrum Disorder: Parent's Essential Guide 2026